ISLINGTON

| THE KING'S

HEAD, ISLINGTON Built in 1543, the

King's Head was founded as a pub theatre in 1970 by Dan Crawford. This

famous and eccentric fringe venue tends towards miniature musicals,

neglected classics and new plays rather than the more radical fare of

other venues.

Famous performers include Victoria Wood, Steven Berkoff, Tom Conti and Anthony Sher. Many shows have transferred to the West End and many have died the death. Decor: Traditional bare-board pub with grand piano, coal fires, old-fashioned theatrical spotlight illumination, etched Victorian glass and original gas lights. The back room auditorium is set up with tables and chairs where customers can dine before the show. Capacity 120 |

The Times 1995

Dan Crawford's eccentric theatrical dreams have enriched us all, says Benedict Nightingale

PULLING PINTS AND PUNTERS

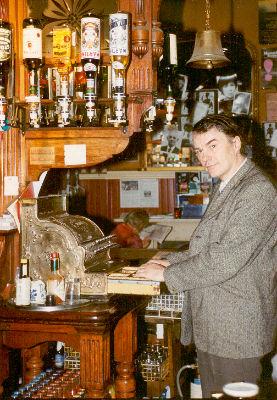

From Hackensack via Ealing to Islington: Dan Crawford "might be vying with Alastair Sim for the role of a vicar"

Which

obsessed

American

expatriate

has

made

the

greatest contribution to the

British theatre in recent years? If you have been paying attention to

these pages, you will probably opt for Sam Wanamaker, whose indignation

at finding Shakespeare’s most famous playhouse commemorated only by a

blackened plaque on a warehouse wall has culminated in the building of

the replica Globe that will be opening in Southwark next year.

If your tastes are more avant-garde you will remember Charles Marowitz, the Mephistophelean New Yorker who created the Open Space in London, or "Gentleman" Jim Haynes, the Southern dandy who launched the Traverse in Edinburgh and the Arts Lab in Drury Lane before becoming a Left Bank guru in Paris.

But let not his own diffident and modest manner tempt us to overlook the claims of Dan Crawford, perhaps the most productive Anglophile and monomaniac of them all. Twenty-five years ago this month he acquired the King’s Head in Islington, and there he launched the first pub-theatre in Britain and, presumably, the world. He has discovered or developed scores of talents, from Anthony Sher to Quentin Crisp, Steven Berkoff to French and Saunders, and transferred nearly 30 productions to the West End. His theatre's production of Burning Blue is now at the Haymarket and his own revival of Noel Coward's Cavalcade opens at Sadler's Wells next week. And it all began, believe it or not, with a boyhood passion for the tacky, batty England of the Ealing comedies.

Crawford was clearly a bit of an oddball in his native Hackensack, the New Jersey town he describes as "like Croydon, only not as pretty". Instead of following his father, a printer, into a blue-collar job, he became a jack-of-all-trades at a local rep theatre run by Robert Ludlum, now well-known as a thriller writer. That was in 1960 and he was just 15. Nine years later he was in England, having learnt his craft as actor, director, and company manager of the Revlon Revue, the Faberge Follies, and other industrial tours.

It was, he says, the offbeat charm of The Lavender Hill Mob and The Man in the White Suit that originally brought him across the water; and, if you meet him, you can still sense why. As he sits vaguely smiling over his tea in a local caff, a safety-pin holding his specs together and a tweed jacket defying the August heat, he might be vying with the late Alistair Sim for the role of a vicar or prep-school master. In 1995 he still drives a green Austin A30. In 1995 he still requires the bar staff at the King’s Head to ask for payment in pounds, shillings and pence. In 1995 he still thinks London “wonderful”.

But to patronise Crawford as some period holdover would be an error. He seems, and perhaps is, a bit eccentric. One of the oddest experiences in London is sitting, after a nice dinner in the King’s Head auditorium usually in a chair designed for an anorexic dwarf and hearing him give the audience his regular welcome. This ends in a high-clipped “thankyou" or "kyoo" that is invariably received with bewildered titters, so much does it sound like an Ealing Comedy duchess opening an Ealing-comedy fete. Yet it took all American enterprise and huge energy to get the place going.

By 1970 Crawford had concluded a) that he wanted his own theatre in London but could never make a living from it, and b) that one way of keeping alive was to run a pub. His genius was to put these propositions together, though not without difficulty. The breweries told him he was mad and the estate agents sent him nothing suitable. So, hearing that Islington was a rising area, he got off one day at the Angel Tube station and walked along Upper Street, dropping into pub after pub in hopes of finding what he wanted.

DAN CRAWFORD was a truly original man of the theatre. As a young American, newly arrived in London, he spotted the potential in a run-down Victorian pub in a North London high street, the King’s Head in Upper Street, Islington, and gave all his energy to making it a cutting-edge venue for new drama, musicals, revivals and cabaret-style revues. Nothing was ever impossible: on a stage 12 feet wide by 6 feet deep, he could contemplate a cast of 18 in a ballroom scene, or 15 set changes for One Touch of Venus.

For 35 years, actors who could have commanded West End salaries went to the King’s Head for a flat rate of £120 a week (£300 today), regardless of fame and status; suffering the indignity of its cramped, not to say non-existent, backstage facilities (“Try sharing a 6ft dressing room and a loo with seven other nervous actors”). All were proud to support Dan Crawford. To play the King’s Head was often a labour of love, but it paid off in peer-group kudos and audience applause. The careers of Ben Kingsley, Rupert Graves, Alan Rickman and Victoria Wood were launched there.

Crawford’s enthusiasm was infectious, but he remained the most modest of showmen: shabbily dressed in rumpled cords and tweed jackets. His organisational skills were shambolic, with a boyish innocence and openness to new ideas that never hardened into cynicism. Nor did he ever acquire the financial acumen of an impresario. What he had instead was heart, doggedness, and an instinct for what would excite actors and draw audiences.

Dan Crawford was born in Hackensack, New Jersey, a place he described as “double Walthamstow”. As a boy he was enchanted by British films, particularly the Ealing comedies: Alec Guinness in The Lavender Hill Mob, George Cole in A Christmas Carol. Hackensack, he used to remind people, was rhymed by Cole Porter with “Never go back”. Life there was “terminally drab” until a repertory theatre came to town when he was a schoolboy of 15. The actormanager in charge addressed him as “dear boy”, invited him backstage and cemented his determination to get to England.

He saved money by working as an actor and stage manager in New York, and in bars and on building sites. In 1969 he arrived in London, planning to run a pub and create the capital’s first pub theatre. He worked in pub bars, and the next year he came across the King’s Head. It was almost derelict, with no landlord, few customers — the manager said working there was like solitary confinement — and had stood untouched and unmodernised since 1938. The pub’s capacious back room had once contained a boxing ring.

After paying a nominal sum for the value of the fixtures and fittings, Crawford deployed his construction skills to knock together a rudimentary theatre, building the stage himself. The big wooden-floored main room, with central bar and open fires at each side, retains its Victorian style today and 33 years after decimalisation the ancient till still rings up the price of beer in pounds, shillings and old pennies. Crawford said he liked the ringing sound of the word “shilling ”.

The first play, Boris Vian’s The Empire Builders, was not a success. The second, a dramatisation of John Fowles’s The Collector, which Fowles himself helped to stage, was a hit.

Scripts began to arrive: in the neophiliac culture of the time, this eccentric new venue, making no concessions to contemporary style, had an eccentric buzz about it. Among the first successes were the charming musical Spokesong, by the Northern Irish writer Stewart Parker, the first dramatic presentation of the Ulster situation, and Kennedy’s Children, by Robert Patrick, both of which transferred to the West End and Broadway.

The breadth and range of the works he chose were full of surprises. He put on Shaw’s Candida, Barrie’s Dear Brutus, Gogol’s The Nose and Stoppard’s musical Rough Crossing. He revived Rattigan’s The Browning Version, the production watched with approval by Rattigan shortly before he died. He introduced new works such as Athol Fugard’s Hello and Goodbye, which won an award for Janet Suzman. Tom Conti, Hugh Grant, Joanna Lumley, Steven Berkoff and Richard E. Grant enjoyed early successes at the King’s Head.

Crawford revived Noel Coward’s sparkling play Easy Virtue, which had lain unperformed since 1927; it transferred to the Garrick and ran for a year. Later he did the same for Coward’s Song at Twilight. Sheridan Morley’s Noel and Gertie made its debut there.

In almost every production — from Tom Stoppard’s Artist Descending A Staircase, which had begun as a Radio 3 play, through George S. Kaufmann’s You Can’t Take It With You, to R. C. Sheriff’s Journey’s End, the acting was outstanding: Crawford threw tremendous energy into casting. For actors, the miniature dimensions of the stage and the closeness of the audience added a palpable intensity to the experience. To sit in the front row and watch Samuel West in Journey’s End was an experience never to be forgotten.

Among the outstanding one-handers was Number One, from New Zealand, in 2004. Solo performers — Corin Redgrave, Sarah Miles, Victor Spinetti, Sheridan Morley, John Julius Norwich — played to full houses, and there were revues and celebrations of individual songwriters such as Dorothy Fields and Jerome Kern. In 1982, Mr Cinders revived the fortunes of the great Vivian Ellis, with whom Crawford enjoyed a close father-son relationship. Later Crawford directed a celebration of Vivian Ellis, Spread a Little Happiness, and then in 1992 revived his 1940s musical, Bless the Bride, with a coda in which Judy Campbell, one of Coward’s favourites, sang Ellis’s most enduring hit song, This Is My Lovely Day.

So varied was the repertoire that a King’s Head theatregoer could remain in N1 and still see performances that ranked with anything on Broadway or Shaftesbury Avenue. Nica Burns, chairman of the King’s Head board, says no theatre other than the National has enjoyed more transfers to the West End.

Latterly Crawford began to direct his own productions. He had always been closely involved: cutting out the middle man drew him even closer. He got on well with actors and they loved him for the attention and weight he gave to every detail of their performances. Crawford would sometimes arrive at rehearsals with sacks of potatoes and chickens for the theatre dinners. Writers were always welcome to watch and make suggestions.

Before each show, Crawford would get up on stage and ask audiences to fling their loose change into a bucket at the end of the evening, to offset the theatre’s loss of its Arts Council grant, which resulted in the Save the King’s Head campaign, led by, among others, Tom Conti and Tom Stoppard and raised in Parliament in May 1991.

No matter how many pennies were collected, neither the seats (rigid pedestals with swivelling velveteen pads) nor the disgusting lavatories ever improved, meaning that the place never lost its grubby alehouse ambience. King’s Head devotees had to be devotees: on hot nights in a full house they were stifled; at other times the air-conditioning almost drowned the acoustics. Joanna Lumley remembers the audience one night making their programmes into paper hats, against the plop-plop of raindrops falling on their heads. So cramped was the dressing-room that backstage affairs flourished, and at least two acting couples, now married, first met there. After the performance the actors, without the protection of a stage door, would emerge into the noisy, crowded pub where a different band would be playing every night.

The spirit of Dan Crawford — dependable, unchanging and much loved — filled the place. Some thought him mad, but in the words of Tom Stoppard he was “stark raving sane”.

Crawford was married four times, but the most enduring — 20 years — was the last. One day in the early 1980s Stephanie, who was married to Matthew Kastin, a former stepson of Crawford’s, arrived in London with their baby, Katey. Crawford fell instantly in love with his stepdaughter-in-law, and they were later married at St Paul’s Covent Garden, the actors’ church.

Stephanie and Katey, who survive him, worked with him in the theatre. Despite prolonged treatments for cancer he was able this year to achieve a lifetime ambition to see the New York Mets in Florida. He died on the eve of Thursday night’s opening of Who’s the Daddy?, the play about multiple affairs in the offices of The Spectator. It was agreed that, as Crawford would have insisted, the show must go on.

Dan Crawford, theatre manager, producer and director, was born on December 11, 1942. He died on July 13, 2005, aged 62

If your tastes are more avant-garde you will remember Charles Marowitz, the Mephistophelean New Yorker who created the Open Space in London, or "Gentleman" Jim Haynes, the Southern dandy who launched the Traverse in Edinburgh and the Arts Lab in Drury Lane before becoming a Left Bank guru in Paris.

But let not his own diffident and modest manner tempt us to overlook the claims of Dan Crawford, perhaps the most productive Anglophile and monomaniac of them all. Twenty-five years ago this month he acquired the King’s Head in Islington, and there he launched the first pub-theatre in Britain and, presumably, the world. He has discovered or developed scores of talents, from Anthony Sher to Quentin Crisp, Steven Berkoff to French and Saunders, and transferred nearly 30 productions to the West End. His theatre's production of Burning Blue is now at the Haymarket and his own revival of Noel Coward's Cavalcade opens at Sadler's Wells next week. And it all began, believe it or not, with a boyhood passion for the tacky, batty England of the Ealing comedies.

Crawford was clearly a bit of an oddball in his native Hackensack, the New Jersey town he describes as "like Croydon, only not as pretty". Instead of following his father, a printer, into a blue-collar job, he became a jack-of-all-trades at a local rep theatre run by Robert Ludlum, now well-known as a thriller writer. That was in 1960 and he was just 15. Nine years later he was in England, having learnt his craft as actor, director, and company manager of the Revlon Revue, the Faberge Follies, and other industrial tours.

It was, he says, the offbeat charm of The Lavender Hill Mob and The Man in the White Suit that originally brought him across the water; and, if you meet him, you can still sense why. As he sits vaguely smiling over his tea in a local caff, a safety-pin holding his specs together and a tweed jacket defying the August heat, he might be vying with the late Alistair Sim for the role of a vicar or prep-school master. In 1995 he still drives a green Austin A30. In 1995 he still requires the bar staff at the King’s Head to ask for payment in pounds, shillings and pence. In 1995 he still thinks London “wonderful”.

But to patronise Crawford as some period holdover would be an error. He seems, and perhaps is, a bit eccentric. One of the oddest experiences in London is sitting, after a nice dinner in the King’s Head auditorium usually in a chair designed for an anorexic dwarf and hearing him give the audience his regular welcome. This ends in a high-clipped “thankyou" or "kyoo" that is invariably received with bewildered titters, so much does it sound like an Ealing Comedy duchess opening an Ealing-comedy fete. Yet it took all American enterprise and huge energy to get the place going.

By 1970 Crawford had concluded a) that he wanted his own theatre in London but could never make a living from it, and b) that one way of keeping alive was to run a pub. His genius was to put these propositions together, though not without difficulty. The breweries told him he was mad and the estate agents sent him nothing suitable. So, hearing that Islington was a rising area, he got off one day at the Angel Tube station and walked along Upper Street, dropping into pub after pub in hopes of finding what he wanted.

In

the King's Head he magically struck, if not gold, at least

workable dross. "It hadn't been decorated since 1938; it had no

clientele; even the winos had deserted it." But it had a Victorian bar

and behind it a room which had variously been used for billiards and

boxing, and could be converted into a theatre.

With just £15 in the till – all that was left from months spent working on building sites he opened the pub in August 1970 and began the process of conversion. The plastering he did himself, the ancient lights and antique red wall coverings he begged and borrowed from other theatres. But somehow he managed to open an absurdist play by Boris Vian. and then his first critical and commercial success, an adaptation of John Fowles's The Collector.

Though the theatre has sometimes teetered on the brink of insolvency, and could not have survived if Crawford had used the bar profits to buy smart suits or new cars, it has ever since been an adornment to London and an example to many pub p1ayhouses that have followed it.

The world or British premieres of Robert Patrick's Kennedy's Children, Stewart Parker's Spokesong, Hugh Leonard’s Da and Stoppard's Artist Descending a Staircase; Denis Lawson in Mr Cinders, Janet Suzman and Ben Kingsley in Athol Fugard, Maureen Lipman in Wonderful Town, Susannah York in Daphne du Maurier's September Tide, Berkoff in his own Kvetch - but need I go on? The King's Head revival of The Browning Version in 1976 began Terence Rattigan's recovery from critical obloquy and, who knows, its touring production of Cavalcade may do the same for the Noel Coward who wrote more serious plays than Private Lives and Hay Fever.

Crawford's policy is to present new and neglected work which strikes him as "humane, tolerant, non-exclusive, capable of belonging to anyone and everyone". That extends beyond straight drama, as a musical about the actor Kean and perhaps a revival of an Edwardian comic opera called The Arcadians should re-emphasise this autumn. It is surprising what can be brought to life on a stage only 20ft wide and l0ft deep with no space for sets or props in wings or flies.

Yet its very limitations explain much of the King's Head's success. There are still some bare floorboards in the pub, still a rough improvised feel to the 125-seat theatre behind it. Like Crawford himself, the place exudes rumpled affability. But that makes for warmth of atmosphere and intimacy of contact between audience and performer. One reason home productions have worked better at the King's Head than in the West End - Friel’s Philadelphia Here I Come, A Shayna Maidel, maybe Burning Blue now - is a loss of that unpretentious immediacy.

Sometimes the proximity of audience, perched on its not-so-comfortable seats and performers crammed on that tiny stage can cause problems. Once Crawford, who still serves behind the bar when he is not directing, was called into the theatre to stop a screaming row that had interrupted a Scots verse play about cannibalism. The actors, maddened by a talkative French critic, had started pelting him with bits of "human" stew and he had responded with the remnants of the spare-ribs he had eaten for dinner. You can’t imagine that happening in a big, posh theatre, can you? And, in a curious way isn’t that a pity?

With just £15 in the till – all that was left from months spent working on building sites he opened the pub in August 1970 and began the process of conversion. The plastering he did himself, the ancient lights and antique red wall coverings he begged and borrowed from other theatres. But somehow he managed to open an absurdist play by Boris Vian. and then his first critical and commercial success, an adaptation of John Fowles's The Collector.

Though the theatre has sometimes teetered on the brink of insolvency, and could not have survived if Crawford had used the bar profits to buy smart suits or new cars, it has ever since been an adornment to London and an example to many pub p1ayhouses that have followed it.

The world or British premieres of Robert Patrick's Kennedy's Children, Stewart Parker's Spokesong, Hugh Leonard’s Da and Stoppard's Artist Descending a Staircase; Denis Lawson in Mr Cinders, Janet Suzman and Ben Kingsley in Athol Fugard, Maureen Lipman in Wonderful Town, Susannah York in Daphne du Maurier's September Tide, Berkoff in his own Kvetch - but need I go on? The King's Head revival of The Browning Version in 1976 began Terence Rattigan's recovery from critical obloquy and, who knows, its touring production of Cavalcade may do the same for the Noel Coward who wrote more serious plays than Private Lives and Hay Fever.

Crawford's policy is to present new and neglected work which strikes him as "humane, tolerant, non-exclusive, capable of belonging to anyone and everyone". That extends beyond straight drama, as a musical about the actor Kean and perhaps a revival of an Edwardian comic opera called The Arcadians should re-emphasise this autumn. It is surprising what can be brought to life on a stage only 20ft wide and l0ft deep with no space for sets or props in wings or flies.

Yet its very limitations explain much of the King's Head's success. There are still some bare floorboards in the pub, still a rough improvised feel to the 125-seat theatre behind it. Like Crawford himself, the place exudes rumpled affability. But that makes for warmth of atmosphere and intimacy of contact between audience and performer. One reason home productions have worked better at the King's Head than in the West End - Friel’s Philadelphia Here I Come, A Shayna Maidel, maybe Burning Blue now - is a loss of that unpretentious immediacy.

Sometimes the proximity of audience, perched on its not-so-comfortable seats and performers crammed on that tiny stage can cause problems. Once Crawford, who still serves behind the bar when he is not directing, was called into the theatre to stop a screaming row that had interrupted a Scots verse play about cannibalism. The actors, maddened by a talkative French critic, had started pelting him with bits of "human" stew and he had responded with the remnants of the spare-ribs he had eaten for dinner. You can’t imagine that happening in a big, posh theatre, can you? And, in a curious way isn’t that a pity?

OBITUARY – THE TIMES

Dan Crawford

Rumpled American who made the tiny King's Head Theatre a venue to rival the best of the West End

December 11, 1942 - July 13, 2005

Dan Crawford

Rumpled American who made the tiny King's Head Theatre a venue to rival the best of the West End

December 11, 1942 - July 13, 2005

DAN CRAWFORD was a truly original man of the theatre. As a young American, newly arrived in London, he spotted the potential in a run-down Victorian pub in a North London high street, the King’s Head in Upper Street, Islington, and gave all his energy to making it a cutting-edge venue for new drama, musicals, revivals and cabaret-style revues. Nothing was ever impossible: on a stage 12 feet wide by 6 feet deep, he could contemplate a cast of 18 in a ballroom scene, or 15 set changes for One Touch of Venus.

For 35 years, actors who could have commanded West End salaries went to the King’s Head for a flat rate of £120 a week (£300 today), regardless of fame and status; suffering the indignity of its cramped, not to say non-existent, backstage facilities (“Try sharing a 6ft dressing room and a loo with seven other nervous actors”). All were proud to support Dan Crawford. To play the King’s Head was often a labour of love, but it paid off in peer-group kudos and audience applause. The careers of Ben Kingsley, Rupert Graves, Alan Rickman and Victoria Wood were launched there.

Crawford’s enthusiasm was infectious, but he remained the most modest of showmen: shabbily dressed in rumpled cords and tweed jackets. His organisational skills were shambolic, with a boyish innocence and openness to new ideas that never hardened into cynicism. Nor did he ever acquire the financial acumen of an impresario. What he had instead was heart, doggedness, and an instinct for what would excite actors and draw audiences.

Dan Crawford was born in Hackensack, New Jersey, a place he described as “double Walthamstow”. As a boy he was enchanted by British films, particularly the Ealing comedies: Alec Guinness in The Lavender Hill Mob, George Cole in A Christmas Carol. Hackensack, he used to remind people, was rhymed by Cole Porter with “Never go back”. Life there was “terminally drab” until a repertory theatre came to town when he was a schoolboy of 15. The actormanager in charge addressed him as “dear boy”, invited him backstage and cemented his determination to get to England.

He saved money by working as an actor and stage manager in New York, and in bars and on building sites. In 1969 he arrived in London, planning to run a pub and create the capital’s first pub theatre. He worked in pub bars, and the next year he came across the King’s Head. It was almost derelict, with no landlord, few customers — the manager said working there was like solitary confinement — and had stood untouched and unmodernised since 1938. The pub’s capacious back room had once contained a boxing ring.

After paying a nominal sum for the value of the fixtures and fittings, Crawford deployed his construction skills to knock together a rudimentary theatre, building the stage himself. The big wooden-floored main room, with central bar and open fires at each side, retains its Victorian style today and 33 years after decimalisation the ancient till still rings up the price of beer in pounds, shillings and old pennies. Crawford said he liked the ringing sound of the word “shilling ”.

The first play, Boris Vian’s The Empire Builders, was not a success. The second, a dramatisation of John Fowles’s The Collector, which Fowles himself helped to stage, was a hit.

Scripts began to arrive: in the neophiliac culture of the time, this eccentric new venue, making no concessions to contemporary style, had an eccentric buzz about it. Among the first successes were the charming musical Spokesong, by the Northern Irish writer Stewart Parker, the first dramatic presentation of the Ulster situation, and Kennedy’s Children, by Robert Patrick, both of which transferred to the West End and Broadway.

The breadth and range of the works he chose were full of surprises. He put on Shaw’s Candida, Barrie’s Dear Brutus, Gogol’s The Nose and Stoppard’s musical Rough Crossing. He revived Rattigan’s The Browning Version, the production watched with approval by Rattigan shortly before he died. He introduced new works such as Athol Fugard’s Hello and Goodbye, which won an award for Janet Suzman. Tom Conti, Hugh Grant, Joanna Lumley, Steven Berkoff and Richard E. Grant enjoyed early successes at the King’s Head.

Crawford revived Noel Coward’s sparkling play Easy Virtue, which had lain unperformed since 1927; it transferred to the Garrick and ran for a year. Later he did the same for Coward’s Song at Twilight. Sheridan Morley’s Noel and Gertie made its debut there.

In almost every production — from Tom Stoppard’s Artist Descending A Staircase, which had begun as a Radio 3 play, through George S. Kaufmann’s You Can’t Take It With You, to R. C. Sheriff’s Journey’s End, the acting was outstanding: Crawford threw tremendous energy into casting. For actors, the miniature dimensions of the stage and the closeness of the audience added a palpable intensity to the experience. To sit in the front row and watch Samuel West in Journey’s End was an experience never to be forgotten.

Among the outstanding one-handers was Number One, from New Zealand, in 2004. Solo performers — Corin Redgrave, Sarah Miles, Victor Spinetti, Sheridan Morley, John Julius Norwich — played to full houses, and there were revues and celebrations of individual songwriters such as Dorothy Fields and Jerome Kern. In 1982, Mr Cinders revived the fortunes of the great Vivian Ellis, with whom Crawford enjoyed a close father-son relationship. Later Crawford directed a celebration of Vivian Ellis, Spread a Little Happiness, and then in 1992 revived his 1940s musical, Bless the Bride, with a coda in which Judy Campbell, one of Coward’s favourites, sang Ellis’s most enduring hit song, This Is My Lovely Day.

So varied was the repertoire that a King’s Head theatregoer could remain in N1 and still see performances that ranked with anything on Broadway or Shaftesbury Avenue. Nica Burns, chairman of the King’s Head board, says no theatre other than the National has enjoyed more transfers to the West End.

Latterly Crawford began to direct his own productions. He had always been closely involved: cutting out the middle man drew him even closer. He got on well with actors and they loved him for the attention and weight he gave to every detail of their performances. Crawford would sometimes arrive at rehearsals with sacks of potatoes and chickens for the theatre dinners. Writers were always welcome to watch and make suggestions.

Before each show, Crawford would get up on stage and ask audiences to fling their loose change into a bucket at the end of the evening, to offset the theatre’s loss of its Arts Council grant, which resulted in the Save the King’s Head campaign, led by, among others, Tom Conti and Tom Stoppard and raised in Parliament in May 1991.

No matter how many pennies were collected, neither the seats (rigid pedestals with swivelling velveteen pads) nor the disgusting lavatories ever improved, meaning that the place never lost its grubby alehouse ambience. King’s Head devotees had to be devotees: on hot nights in a full house they were stifled; at other times the air-conditioning almost drowned the acoustics. Joanna Lumley remembers the audience one night making their programmes into paper hats, against the plop-plop of raindrops falling on their heads. So cramped was the dressing-room that backstage affairs flourished, and at least two acting couples, now married, first met there. After the performance the actors, without the protection of a stage door, would emerge into the noisy, crowded pub where a different band would be playing every night.

The spirit of Dan Crawford — dependable, unchanging and much loved — filled the place. Some thought him mad, but in the words of Tom Stoppard he was “stark raving sane”.

Crawford was married four times, but the most enduring — 20 years — was the last. One day in the early 1980s Stephanie, who was married to Matthew Kastin, a former stepson of Crawford’s, arrived in London with their baby, Katey. Crawford fell instantly in love with his stepdaughter-in-law, and they were later married at St Paul’s Covent Garden, the actors’ church.

Stephanie and Katey, who survive him, worked with him in the theatre. Despite prolonged treatments for cancer he was able this year to achieve a lifetime ambition to see the New York Mets in Florida. He died on the eve of Thursday night’s opening of Who’s the Daddy?, the play about multiple affairs in the offices of The Spectator. It was agreed that, as Crawford would have insisted, the show must go on.

Dan Crawford, theatre manager, producer and director, was born on December 11, 1942. He died on July 13, 2005, aged 62