EQUALLY DIVIDED by

Ronald Harwood

Venue: Watford Palace 2013

Directed by Brigid Larmour

Venue: Watford Palace 2013

Directed by Brigid Larmour

| Edith Taylor |

Beverley Klein |

| Charles Mowbray |

Walter Van Dyk |

| Renata Taylor | Katharine Rogers |

| Fabian Hill |

Gregory Gudgeon |

Reviews

Daily Telegraph

A family death always lays bare those that are left behind, and what it reveals is not necessarily pretty – particularly when there is money at stake. The contents of a will can bring out a sudden venality in the most apparently unworldly people. This vexed issue of family inheritance is at the heart of Ronald Harwood’s four-hander, first performed in 1998.

Two sisters, downtrodden Edith (Beverley Klein) and glamorous Renata (Katharine Rogers), reunite after their mother’s death at her bizarre house made of old railway carriages, and learn from the local solicitor (Walter van Dyk) that her estate is to be divided equally between them. This seems fair, but is it? Edith is poor and Renata is rich. Edith has been her mother’s carer, while Renata has merely been her daughter. It is impossible to argue that Edith does not deserve the inheritance more than Renata, but is inheritance really a question of deserving? Furthermore, would it be right for Edith to deny a dying woman’s wishes and fight for her own future, to make underhand use of the mysterious antiques expert (Gregory Gudgeon) who sees potential in her mother’s vast collection of bric-a-brac? These are the themes the play examines, with the central role of Edith an intriguing Anita Brookner-type character who gradually grasps that her qualities of meek goodness merit scant reward in a world that values brash, bold Renata.

All of Ronald Harwood’s work – from his breakthrough play The Dresser to the recently filmed Quartet – is characterised by a kindly, humane perceptiveness, and Equally Divided is no exception. Nevertheless it is not a substantial piece. Indeed it feels like a one-act play that has been unnaturally extended. Its wordiness, however eloquent, cannot disguise the fact that another dimension is lacking, whether it be a complicating sub-plot or simply a less inevitable progression of events.

This production by Brigid Larmour, artistic director at Watford Palace, makes some use of the effectively bleak, low-ceilinged set (by Ruari Murchison), and allows Beverley Klein a strong moment of pathos when she recalls the passionless one-off encounter that comprises her emotional history. On the whole, however, the piece is played for laughs, rather in the style of a sitcom, as when much business is created from Renata’s flagrant smoking and Edith’s frenzied window opening. Harmlessly entertaining, but perhaps not the best way to elicit theatrical subtleties.

* *

* * *

What's on Stage

Money may make the world turn around more smoothly on its axis but it can create an avalanche of jagged emotions within a family. Take the two sisters in Ronald Harwood's 1998 comedy – though tragicomedy might be a fairer description. Their parents were refugees from Hitler's Europe but are now dead, their mother only recently. They appear to be joint inheritrices, though their life patterns have diverged extraordinarily.

The sister we meet first is frumpy Edith, the stay-at-home daughter – home being a south-coast house made out of old railway carriages. She has been her mother's companion and, latterly, her carer. Renata flew the nest early on, has made wealthy marriages (and even more lucrative divorce settlements); she simply came for the funeral and the reading of the will. That vital document is in the care of the family solicitor Charles, a widower with an attention-span strongly resembling cotton-wool. Laughs there are a-plenty, but the underlying dilemmas for all three – and for the actor-turned-antique-dealer invited by Edith to give an independent valuation – are serious enough. We all know carer-daughters who somehow miss out on the lives their siblings enjoy. Some of us have had dealings with solicitors whose mental world seems so far removed from that of their clients that you wonder how they ever managed to pass the Law Society's examinations. And, as for the antiques expert...

Brigid Larmour's production gives a fair crack of the theatrical whip to each character in turn. Beverley Klein's Edith dominates – and you end up being completely on her side, though her two monologues do tend to be over-stretched out. But it's a rounded portrait of someone who, both in real life and onstage, can be treated as someone easily passed over and ignored. Katharine Rogers has the right sort of spiky elegance as Renata, a worldly woman who knows her rights – and can judge a man (any man) in an instance. If Charles bumbles and fumbles, and Walter van Dyk certainly makes him the epitome of that, then Gregory Gudgeon as Fabian is Lovejoy with quotes, spouting verse at the drop of a cue in between checking makers' marks on anything from a Hepplewhite table to a coffee pot or enamelled miniature. Gudgeon has in many ways the easiest part; you know from the beginning that Fabian is a rogue, but you warm to his own enjoyment of his preposterous personality.

The set by Ruari Murchison is long, low and narrow. It suggests its inhabitants' ability to combine a degree of improvisation and making-do with an all-important gemütlich. Now what was a home with comforts has become a prison, for Edith at any rate. Harwood leaves us guessing as to how she will escape, if she does. We are, after all, in 1997, which was supposed to mark the start of a brave new world. I wonder what happened to it.

Bucks Herald

Opinions are likely to be equally divided over the moral dilemma thrown up in Ronald Harwood’s play about warring sisters squabbling over the estate of their mother. The premise behind Equally Divided, at Watford Palace Theatre, isn’t new but perhaps the re-telling of the story is.

For the past 15 years Edith, a dowdy 50-something spinster, has cared for her invalid mother in a ramshackle seaside home made from redundant railway carriages. Typically she has sacrificed her own chance of happiness, love and a career to be the stay-at-home carer and she is bristling with resentment and jealousy - for no matter what she did the old battle-axe, who had a penchant for collecting antiques, favoured Renata, the glamorous other daughter.Now the old girl is gone and Renata and Edith discover that the estate, such as it is, is being equally divided.It’s a bitter blow to Edith who has no savings and was relying on the will to carry her through her old age. Renata, on the other hand, has homes in London and France, a multi-million pay-off from a divorce and is sitting very comfortably. What’s more, she had left Edith to cope with mother while she went off and had a life. It’s all so unfair.

Director Brigid Larmour has coaxed some fine performances from her cast of four. Beverley Klein, as Edith, has the lion’s share of the work. On stage pretty much throughout the 110-minute drama she gives an engrossing performance as a honest women consumed by jealousy.“The theme of the 20th century,” she says, “is the shallowness of decency” and it turns out that perhaps desperation forces the most decent into moral corruption.

Katharine Rogers as Renata has little to do other than behave outrageously. She has one moment of clarity, between glasses of vino, when she tries for an earnest conversation with her sister that serves to reveal the cause of the women’s animosity to each other. The two men on the scene, wet solicitor Charles (Walter Van Dyk), and actor turned antiques dealer Fabian (Gregory Gudgeon) are little more than window dressing but I enjoyed Gudgeon’s performance as “an old rogue” who, one hopes, might give Edith the happy ending she craves. All the characters are deeply flawed and sympathies change as they reveal more of themselves. It’s a thought-provoking and deceptively complex little piece that takes a while to engage, picking up nicely in the second act.

* *

* * *

Daily Mail

Daily Mail

Sir Ronald Harwood’s deceptively gentle Equally Divided argues that justice is sometimes reached only by breaking the law. This may be a principle common in great political struggles, but here the story is more domestically humdrum: two adult sisters are hearing the will of their eccentric mother, who has just died leaving a haul of antiques. The estate is to be divided equally between impecunious spinster Edith (Beverley Klein) and her rich, much-married sister Renata (Katharine Rogers). Edith looked after ‘Ma’ for ages; Renata barely lifted one of her painted fingernails to help the old dear.

With the opening scene a telephone monologue, things take a while to get bubbling and the pace is never exactly frenetic. I did not mind. After a long day, I was content to listen to Sir Ronald’s intelligent lines (‘A will is the dead trying to control the living’) and enjoy Ruari Murchison’s set. The action takes place in the family residence: an old railway carriage on a beach in Southern England in 1997. The place is cluttered with objects, including the mother’s bath chair. Is the sight of a dead person’s empty wheelchair not somehow affecting? It’s the old cushion that always gets me. The family solicitor turns up, forgetful, not as harmless as he at first seems. Walter van Dyk is good at catching this man’s mouldiness, but he could work harder at the character’s selfish gene. Fourth, we meet a disarmingly dishonest antiques dealer played by Gregory Gudgeon. At first too foppish, he grew on me, as, indeed, did the entire show. The whole thing is delightfully understated.

As for the morality of justice via crime, it is somehow refreshing to behold criminal tendencies in distressed gentlefolk. Why should drab losers not cast off their victimhood? Miss Klein’s Edith transforms successfully from doormat to something more assertive, yet still not overly proud. Not even the most baleful of those purple-nosed judges at the Garrick Club would condemn her, surely.

* *

* * *

Watford Observer

In this human, almost black comedy by Ronald Harwood, two sisters are reunited in the railway carriage home of their recently deceased mother. One, the dutiful, downtrodden Edith (Beverley Klein), has never left the claustrophobic family home, acting as her mother’s carer for the last 15 years. The other, the flighty, wealthy, glamorous, overemotional Renata (Katharine Rogers) has lead a full life, leaving a long line of husbands in her wake. Brought together again, tension mounts, tempers flare and the past is pulled painfully into the present as the matter of their inheritance, tied up in their refugee mother's antiques, comes to the fore.

Sibling rivalry is a unique thing, and Klein brilliantly captures all of its bottled-up bitterness in a sigh or a glare. It's in these subtle crackles of hostility between the sisters that the play really sparkles and Edith has our sympathy being in the incredibly frustrating situation of seeing the worst in someone when all around refuse to notice. Rogers is perfect in her role, creating a character both captivating and intolerable. The superbly crafted set by Ruari Murchison puts the characters into a confined space, forcing them to rub up against each other, adding literally to the friction between them. Through the windows nothing but the impending grey fog while the antiques sitting precariously on the shelves add to the sense that at any time, all could come crashing down into chaos. The arrival of the handsome, widowed family solicitor (Walter Van Dyk) and a mysterious eccentric antiques dealer (Gregory Gudgeon) brings a plot of double crossing into play - or is it simply justice? The right and fair thing? Well that depends...

The audience, though they might not want to admit it, recognise the worst in all of them as green eyes and greed take over, but what's really driving them all is loneliness and fear of it, the desperate hope of a brighter future. The script sways from comedy to tragedy, at times a little too wildly, but these consummate performers are able to keep things on track. It's infectiously funny, brimming with devilish deeds and moral dilemmas and not afraid to plummet the depths of pain. You'll struggle to align right and wrong - but you'd be absolutely right to go and see it.

* *

* * *

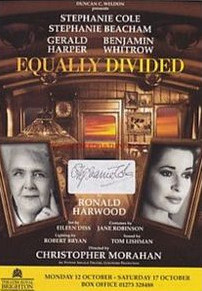

Note: The original 1998 production featured Stephanie Cole, Stephanie Beacham, Gerald Harper and Benjamin Whitrow. It was directed by Christopher Morahan and toured the UK including Richmond and Theatres Royal Brighton and Bath.