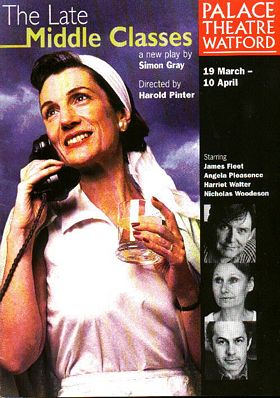

| Thomas Brownlow | Nicholas Woodeson |

| Holliday Smithers Charles Smithers |

James Fleet |

| Celia Smithers | Harriet Walter |

| Holliday Smithers as child | Sam Bedi |

| Ellie Brownlow | Angela Pleasence |

Review

Guardian: Michael Billington

Ten years of solitude

Harold Pinter is famous for his pauses. Who better to direct a play about a decade when all emotion was put on hold?

The fifties are back in fashion. Along with a Conran exhibition, From The Bomb To The Beatles, we now have a new Simon Gray play, The Late Middle Classes, that harks back to post-war values. Although it's a slow-burning work, it evokes with racking fidelity a period when emotions were as carefully rationed as eggs and butter. One also detects a touch of autobiography: like his child protagonist, Gray was born on a small Hampshire island and boasts the unusual Christian name of Holliday. And although the play is framed by two short scenes set in 1982, the bulk of the action takes place 30 years earlier. What Gray carefully charts is the repressions of the period. Holly's father is a pathologist and his mother a queen of the local tennis club, and although outwardly affectionate, their marriage contains its own subterfuges. Even more crucially, the love that Holly's bachelor Austrian music teacher clearly feels for the boy is treated as something dirtily disgusting.

In writing about the fifties, Gray consciously apes its dramatic forms. I don't mind the echoes of Rattigan or a play like Philip King's Serious Charge, in which a vicar was accused of what the News Of The World used euphemistically to call "interference". But audiences today are quicker on the uptake than in the fifties, and Gray spends too long on exposition before getting to the dramatic meat. When he does finally arrive, he has a vital point to make: that, in a repressed world, children become the vehicles of adult passion. Celia, Holly's over-bred, under-educated, emotionally starved mother constantly begs the boy to declare his love for her. And the piano teacher, tethered to his sherry-swilling immigrant mother, finds in Holly an outlet for his own thwarted affections. In the past Gray has often seemed an acerbic observer, but here he shows unusual sympathy for the sexually and emotionally solitary.

Harold Pinter, directing his eighth Gray play, also gets the details exactly right: not just the obvious things like a father's shyness about discussing sex with his son but, even more importantly, the sense of guilt that pervaded fifties life. In the play's most resonant line, Nicholas Woodeson, as the piano teacher who delights in inflicting disciplinary games on the boy, says: "It is through the punishment we shall find the sin." More than all the references to powdered eggs or the Third Programme, that line brought back to me in a flash the decade's aroma of culpability. But Woodeson's is only one in a set of first-rate performances. Harriet Walter as Celia marvellously evokes the pathos of the middle-class woman who, trained for nothing except marriage and motherhood, is forced to dramatise her own essentially vacant life. James Fleet as her pathologist husband artfully suggests a man more at ease with the dead than the living. Angela Pleasence as the piano teacher's mum, furtively hiding her drink or cowering in terror at every knock at the door, adds to the atmosphere of guilt, and Sam Bedi is simply extraordinary as the Jamesian Holly who views adult manoeuvres with unnerving impassivity.

Mae West famously liked a guy who took his time. Mr Gray certainly does that. But, in the end, he recreates the furtiveness and shame of the fifties with almost eerie exactitude.

Footnote

In a review of The Late Middle Classes' West End premiere in 2010, Libby Purves wrote in The Times: Grayís 1999 play opens at the Donmar pre-loaded with righteous critical indignation: in its first appearance at Watford it won Best New Play, but its West End run at the Gielgud theatre was dropped to make room for a musical about a boy band (which flopped). Harold Pinter called that "an act of betrayal and disgrace to English theatre" and for once he wasnít putting it too strongly. This play should not have been silent so long: the sadness is that its author didnít live to see this fine production. It says something valuable about a much-mocked generation.

Report in The

Guardian 13 May 1999 by Sue Quinn

The playwright and director Harold Pinter yesterday launched a vitriolic attack on one of London's West End theatres following its decision to snub his latest production, The Late Middle Classes in favour of a rock musical. Pinter described as 'an act of betrayal' and a 'disgrace to English theatre' the move by the Gielgud Theatre to abandon plans to stage his play and to opt instead for Boyband, a rock musical about a group of boys ambitious for pop stardom.

The decision not to proceed with the play, directed by Pinter, written by Simon Gray and starring Harriet Walters, means it will now never make it to the West End, despite its 'stellar team', sell-out regional run and several highly favourable reviews. 'One does have a deep sense within the whole company of shock, and in fact, of betrayal,' Pinter said last night. 'The Gielgud was very enthusiastic and then suddenly, what I recognise to be a very, very fine piece of work, is treated like this. I think we have been treated very, very badly, and I think it's a disgrace to me, the production and to English theatre.' Pinter said he had no idea why negotiations with Stoll Moss, the theatre company which owns the Shaftesbury Avenue theatre, broke down. But The Late Middle Classes had enjoyed a successful regional run. 'In Brighton it did extremely well, in Watford it broke all records, and Richmond is sold out as well. How more commercial can one get? I think the Gielgud has made an inexplicable decision and a disgraceful one.'

The Late Middle Classes, a bitter-sweet story of a young boy 'caught between two types of oppressive love' in 1950s England, won some glowing reviews when it opened at the Palace theatre in Watford last month, although it was slated in a review in the Sunday Times. But Nica Burns, production director for Stoll Moss, said the decision to abandon plans for the run came when 'negotiations broke down' two weeks go. She rejected suggestions that the decision was made because the play was deemed to be lacking commercial appeal. 'I loved the play and thought it was brilliant and we were very enthusiastic,' Ms Burns said. 'But there were four key points of the negotiations that we just couldn't come to terms with, and they had to do with the length of the run and issues relating to the availability of the actors.' Ms Burns said Boyband had been chosen because 'I was facing a dark theatre. It's completely out of order to cast the Gielgud management as the bad fairy in all of this.'

A spokesman for Gray said: 'He's very sad. He just can't imagine why this should happen after the response in Watford.' Producer Sonia Friedman, from production company ATG Turnstyle, said everyone involved in the production was devastated that it would never be seen in London. She added: 'It's a very high quality piece of work and it's rare to get together this quality of director, writer and cast. It's very sad for the West End that it's not going to be seen.'