THE

MISER

by

Molière

Translated by Ranjit Bolt

Venue: Richmond 1995

Director: Nicholas Broadhurst

Venue: Richmond 1995

Director: Nicholas Broadhurst

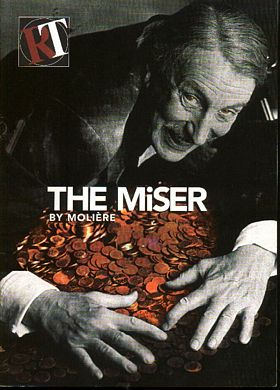

| Money and avarice truly are the roots of all evil in Molière's hilarious observation of the flawed human character. Harpagon has everything that a man could want but his fixation with money threatens the happiness and future prospects of his entire household. Unsettled marriage settlements, mistaken identities and Harpagon's number one obsession collide in a contest of wit and wills. Ian Richardson makes his long-awaited return to the stage in this classic comedy. | |

| Characters in order of speaking | |

| Elsie | Lucy Robinson |

| Valere | Simon Coates |

| Claudine | Charlotte Randle |

| Cleante | Ben Miles |

| Harpagon | Ian Richardson |

| La Fleche | Mark Hadfield |

| La Merlouche | Alexander Nash |

| Simon | Philip Bond |

| Frosine | Victoria Kempton |

| Jacques | Julian Forsyth |

| Mariane | Sara Griffiths |

| Detective | Terence Lodge |

| Policeman | Richard Buss |

| Anselme | Philip Bond |

Review

Times: Benedict Nightingale

Losing something in the translation

Moliere’s Miser may open with a love scene, but that does not intimidate Nicholas Broadhurst the director who precedes it with ten minutes of dumb-show. Down the rickety stairs stumbles Ian Richardson’s Harpagon in a towelling dressing-gown apparently stolen from the Hotel George V. He tests his DIY burglar alarm, a blend of Geiger counters, lights and sirens, and uses the contents of last night’s hot-water bottle to make coffee. Then in comes a lackey dressed in Tour de France yellow, pumps away at the pedals of an antique bike that stands in a cupboard, and suddenly we see why wires and car-batteries are all about. Why enrich the electricity company when human oomph can light one-bar heaters more cheaply?

It is funny, and it is symptomatic. The Miser was one of Moliere’s mature pieces, written long after he had begun to renounce knockabout farce for satiric comedy. But I bet there were people in the Paris audiences of 1668 who still wished that Moliere was more generous with visual fun. In many ways Broadhurst’s production and Simon Higlett’s splendidly tacky décor are aimed at their English descendants.

Consistently enough, Richardson does not give us a thin, mean miser like Charles Kay’s at the National four years ago. His Harpagon is a plump eccentric who, especially when he crams a black helmet onto his head and rushes into the garden to shoot the dog he fears is unearthing his buried cashbox, seems reminiscent of his namesake, the late Sir Ralph. For once you can see why the miser’s chef-chauffeur-handyman-factotum is fond of the old boy. Yet it is obvious there is loss, and that part of the loss is Moliere. Myself, I enjoyed many of Richardson’s pottier doings, such as his wooing of the wretched Mariane in a bemedalled frock-coat, first spryly crashing down the stairs into a pile of plastic sponges he has presumably bought at a discount, then creakily overacting the senile oldster in hopes this will convince her she may soon inherit. But where is the chilling monomaniac who rejects kin for gain? Nowhere; for the translator, Ranjit Bolt, has added a jokey sentimental coda involving Harpagon and the matchmaker Frosine.

Actually Bolt, so often brilliant, is not at his best here. Even without him, the updating might create difficulties – why, for instance, should grown children be so helplessly in awe of their father in Paris 1995? But the contemporary references up to and including Prince Charles’s marriage, sometimes seem slick, easy and, worse, vulgar. I don’t greatly mind Harpagon being called a “parsimonious old git”, but I do wonder if this bumbling figure, in ancient tweed, would himself call his son Cleante “ a little shit” and “miserable turd”, or bark “don’t give me that crap” at him.

Still, Ben Miles’s restless, volatile Cleante is one of the evening’s successes. Mark Hadfield, Julian Forsyth and Simon Coates are strong too. And when the translation gets too strenuous, there is always the set to enjoy. How does the household get its water? Why, from a pipe that runs from the bucket that collects whatever rain falls through the holes in the glass roof. That would be a funny idea if the play were set in 1668 or 1995, AD or BC.