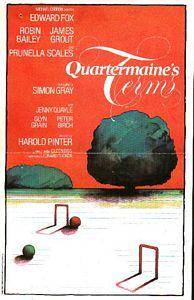

Cast

Edward Fox, Prunella Scales

Edward Fox, James Groust

Reviews

The Times: John Russell Taylor

* * * * *

* * * * *

| St John Quartermaine |

Edward Fox |

| Melanie Garth |

Prunella Scales |

| Henry Windscape |

James Grout |

| Eddie Loomis |

Robin Bailey |

| Mark Sackling |

Peter Birch |

| Derek Meadle |

Glyn Grain |

| Anita Manchip |

Jenny Quayle |

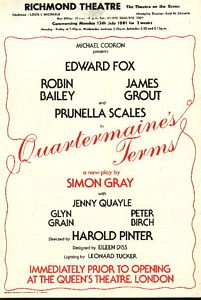

Edward Fox, Prunella Scales

Edward Fox, James Groust

Reviews

The Times: John Russell Taylor

Simon Gray is a very clever playwright; he is just not always very interesting. Quartermaine’s Terms is a case in point. It covers about three years in the life of an English-language school for foreigners in Cambridge during the early 1960s, all from the angle of the staffroom. Hence, though we hear alarming tales of tearaway Japanese and rebellious Germans demanding value for money, we see only the co-principal, five permanent members of staff, and the new part-timer who gradually settles in. They are, no doubt about it, well observed in terms of their speech-patterns and their intricately unsatisfactory relations with one another. And the way that we gradually find out about their out-of-school activities, their nearest and dearest and how they hate them, and the tempestuous dramas which go on in nearly all their lives outside the safe confines of the school, is very ingenious to say the least.

Actually it is also to say the most. None of the characters is exactly unbelievable. But we never get near enough any of them to care whether they live or die – or for that matter what happens to Melanie’s horrible old mother or Henry’s neurotic swot of a daughter (both of whom come to sticky ends off-stage). The play is never quite boring (like Close of Play), but it does not ever (unlike Butley or Otherwise Engaged) quite catch fire.

It comes nearest in the scene where Prunella Scales, as the unfortunate Melanie, breaks down and pours out her resentments about life to her (we gather) one time suitor Henry (James Grout). And here it seems to be more the force of the performance than what is waiting there in the text. This moment does suggest, though, that if Harold Pinter had relaxed his directorial control a bit to give more of the fine cast their heads, the text could have been considerably brightened.

I do not know, even so, what anyone could have done with the character of Quartermaine, one of those people who are so slow and stupid and unresponsive to the outside world that, for all their fundamental niceness and decency, you just want to shake or kick them. Edward Fox plays him perfectly, in the requisite slow motion. But how can anyone be made to care? The gay interest in this play (of course with Simon Gray’s work there has to be some) centres on the co-principles, of whom we see only Eddie, a nicely acidulous performance from Robin Bailey as he gradually slides into decrepitude, though we hear and surmise a lot about Thomas, the other half. Not much to be going on with, really; but perhaps we shall have better luck next time.

* * * * *

Observer: Victoria Radin

On transfer to Queen’s

Holy idiot

On transfer to Queen’s

Holy idiot

Simon Gray's Quartermaine's Terms takes that peculiarly English stance of morose satisfaction with the blighted lives that we all must, perforce of course, inhabit. He has thrown together seven characters (now rather a luxury offering in the West End) in the staff room of an English language school in Cambridge. For no apparent reason, and at times anachronistically (did they have family-therapy sessions and were abortions so easy to get ?), the time is the early sixties.

Each character undergoes some private tragedy, which is uncharacteristically blurted out – since part of the tragedy is that it is strictly not done to relate it - in a moment of unwanted confessional to one or two others. The stories are familiar, but in some cases ring true enough. The unmarried Melanie's particular skeleton is her dominating mother, a former philology professor, whose stroke has reduced her to whispered imprecations from the corner of her mouth, like a gangster. The humanistic Henry’s source of despair is his daughter, who goes mad under the pressure of sitting for 0-levels.

Mark's wife does a bunk as he begins the penultimate draft of the novel that never will be published; Anita, less plausibly (we are now sliding down the scale of plausibility), endures three abortions and the spectacle of her husband's flagrant infidelity. Eddie, the joint-principal, a shadowy figure whose chief characteristic is to gain in decrepitude as the play marches over its three-year period, waves a stiff upper-lip when the other (unseen) joint-principal, presumably his homosexual lover, dies in their flat upstairs. Two characters are exempt from private tragedy. One is Derek, whose degree from Hull University (the others, presumably, are graduates of Cambridge) makes him, in this context, grotesque: Gray manufactures a red nose in the form of his accidents (splits in trousers, plasters adhering to various visible parts of his anatomy) and a wife with a fairly severe speech impediment.

The other character is St John Quartermaine, after whom the play is named and whose lonely figure silently opens and closes it. Quartermaine has neither wife nor family nor friends. He loons vaguely round the staff-room, offering - as much as by way of killing time as out of the desire to be of help - to baby-sit someone else's children, serve as sounding-board for other people's marriage problems, or to nurse another's mother. Gray shows him rejected when the going is good, but petitioned when it isn't. But Quartermaine also happens to be a terrible teacher. When the chips are down, it's this brother-to-all; this necessary anonymous glue of the staff-room, who gets the chop.

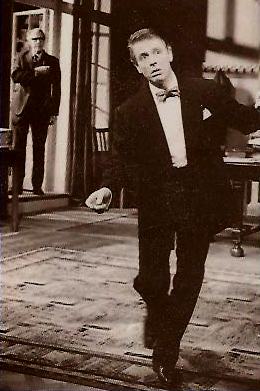

Edward Fox, wearing a series of wickedly well-cut garments and coiffures (Quartermaine's vagueness obviously doesn't extend to his tailor or barber), endows him with a beatific smile that rarely wavers, vowels so precious they gleam like Lady Di's tiara, a charming rather than irritating absence of mind, and the ability to doze off graciously in the lugubrious, faded~green staff-room designed by Eileen Diss as if it were a St James's club. He is most touching as he tries, usually clumsily, to make things easy for others even when they happen to be sacking him.

He is a kind of holy idiot, whose existence, though apparently gratuitous, is necessary for the lives of the other, more selfish mortals. Gray, always the snob, seems to be making a strange equation of this Dostoevskian figure with the class of Englishmen whose existence alone used to be felt to be enough (and which sheds a different light on the Event of Wednesday). He is a new and interesting character to place on the stage; but the trouble is that the author is on much more intimate terms with megalomaniacs like Butley or the Simon of ‘Otherwise Engaged ' -and, indeed, the other characters in this play.

It is like seeing an unhewn lump on a wall of gargoyles. None of these engage us much either, and the quantity of red herrings thrown in the pursuit of laughs puts the brake on any narrative thrust: the five scenes end with a misleading bang or palely loiter. Harold Pinter, directing, invests the production with a beautifully measured pace and the idea of a meaningful sub-text which constantly blows away: what he should have done was gently steer Mr Gray back to his desk and ask him to re-write it.

Prunella Scales's desperate spinster (another red herring: did she or didn't she murder her mother?), James Grout's balloon-waisted humanist (a shambolic version of Butley and Co) and Robin Bailey's bird-like principal are excellently-judged performances in a production which includes some middling ones.

The Times: Ned Chaillet

On transfer to Queen’s

On transfer to Queen’s

Doors never really close in a Simon Gray play. The pretence that his characters seek solitude has been a recurring flaw in his work, and the most popular play, Otherwise Engaged, was irritating in its presumption that the central character wanted quiet to listen to a recording. He could have locked the doors and taken the telephone off the hook and had some peace. There is no such pretence in Quartermaine’s Terms: the doors of staff room at a school of English for foreigners are never shut, but open into the school and remain wide open to the green of Cambridge, in the spring, summer and autumn terms.

There is a quality in that openness that somehow liberates the characters. Stripped of dramatic pretence, they can be observed in a leisurely fashion and Mr Gray's selection of details and exchanges is immaculate: he achieves drama and mystery in mundane lives; the comedy is beautifully stated and even personal tragedies are underlined with running gags that ring with truthfulness. No false hothouse effect is necessary to make bare the bewilderment spirit of his central figure, the grinning, forgetful and deeply kind staff lecturer, St John Quartermaine, an inarticulate character of awesome loneliness who rivals the tragic force of Willy Loman.

His abstract good cheer and eager accessibility do not invite the sought-for intimacy from his colleagues. The elderly principals of the school tolerate him as a wayward member of their academic family, although his classes, even dictation classes, are said to he conducted in absolute silence and he cannot remember the names or nationalities of his students. He is exploited as a babysitter and turned to as an outsider with the assumption that he will always be available; although clearly held in affection, he is permanently remote, yet whether politely excusing himself from a private conversation or hopelessly seeking companions to share his tickets to the theatre, he is a fascinating presence, intensely watchable through the coiled energy of Edward Fox's performance.

Mr Fox is extraordinary. With the exception of one strange, dark anecdote about swans and fear, his dialogue is hardly expressive, consisting of ritualised "absolutelys" and polite phrases, yet he signals deep private amusements and sympathies: his grin of cheer is like a mask of tragedy turned upside down. Regularly sunk deep in an armchair, he seems to be living a past life of aspirations and desires; stirred to conversation he offers a natural affability and a smile devoid of hope. One longs for his repressed articulacy to rage in that school of English, but the depths are clear in his face.

Harold Pinter has gilded the stage with performers of equal worth, living explicitly dramatic lives against the quiet mystery of Quartermaine. Against his reticence they lament the madness of a child, the failure of a marriage: they reveal the apparent murder of a mother and the inadequacy of a struggling writer. It is done with laughter and memorable, visual flare by Robin Bailey, Prunella Scales and the rest.