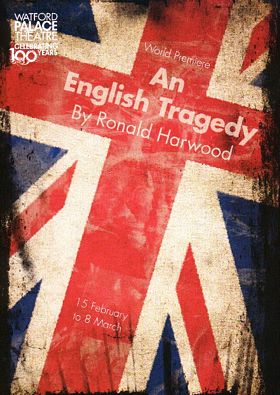

WORLD PREMIER

AN ENGLISH TRAGEDY by Ronald Harwood

Venue: Watford Palace 2008

Director: Di Trevis

AN ENGLISH TRAGEDY by Ronald Harwood

Venue: Watford Palace 2008

Director: Di Trevis

Cast

| Leo Amery |

Jeremy Child |

| John Amery |

Richard Goulding |

| "Bryddie" Amery |

Diana Hardcastle |

| Dr Rosemary Pimlott |

Lucinda Millward |

| Mr Taylor |

Nicholas Rowe |

| The Major |

Michael Fenton-Stevens |

| The Warder |

Bill Thomas |

| German Broadcaster |

Alexander Doetsch |

REVIEWS

THE TELEGRAPH

An English Tragedy: Emotionally devastating tale of a very English fascist

Charles Spencer reviews An English Tragedy at Watford Palace Theatre

An English Tragedy: Emotionally devastating tale of a very English fascist

Charles Spencer reviews An English Tragedy at Watford Palace Theatre

Ronald Harwood is an uneven writer, and I have sometimes been unkind about his work. But when he is on form, he has a rare gift of combining intellectual rigour with profound emotion. He is also one of those increasingly rare devotees of the old-fashioned, well-made play.

At 73, the author of The Dresser and Taking Sides is on a roll. He picked up a Bafta last week for his screenplay for The Diving Bell and The Butterfly, and flies off to Los Angeles this Friday to discover whether he has won the Oscar, too. If he does, it will provide a companion for the one he received for The Pianist. Nor would I be surprised to see this fine new play, An English Tragedy, transferring to the West End, Harwood's natural habitat. It tells a gripping true story with simplicity and power, and somehow manages to move the audience while also making its flesh creep.

The main character, John Amery, appears to have been a cross between Lord Haw-Haw and Sebastian Flyte from Brideshead Revisited. The son of Leopold Amery, a member of Churchill's Cabinet, and the older brother of Julian Amery, the long-serving Tory MP, John was, in contrast, a thoroughly bad egg. He may have been kind to his beloved teddy bear, taking it to cafťs and restaurants and buying it drinks and comics, but he was also an anti-Semitic fascist who broadcast Nazi propaganda to Britain from Berlin, and tried to persuade British POWs to fight alongside the Nazis.

In his personal life he was promiscuously bisexual and enjoyed being tied up and thrashed by rough trade. In 1945 this unsavoury specimen was arrested in Italy and put on trial for high treason at the Old Bailey. There were two defences that would probably have got him off - first, that he was a mentally ill moral defective, and second that he had become a Spanish citizen while helping Franco, and therefore couldn't be charged with treason in England. But Amery astonished his legal advisers and his family by pleading guilty and was hanged by Albert Pierrepoint. The standard explanation was that Amery didn't want to embarrass his relatives - but, as Harwood points out, he could hardly have embarrassed them more already.

Instead the dramatist finds the roots of John Amery's self-incrimination in the fact that though he kept it secret to facilitate his political career, Leo Amery was in fact half-Jewish and his anti-Semitic son was aware of the fact. As a consequence, John became the victim of both an Oedipus complex and a corrosive self-hatred. In the clear light of day this may sound like glib pop psychology, but in the course of the play it proves persuasive thanks to the emotional depth of both writing and acting.

The hot newcomer Richard Goulding gives a virtuosic performance as John, superficially charming, witty and camp in the best Brideshead manner, but with a constant edgy neuroticism about him and sudden scary glimpses of the truly psychopathic. Jeremy Child is superbly moving as his father. The scene in which this reserved Establishment figure suddenly breaks down in choking tears as he discusses his first-born with a psychiatrist is extraordinarily affecting, as is his heroically dignified farewell to his son, where the combination of English reticence and raw anguish put me in mind of Rattigan at his greatest. Diana Hardcastle is deeply touching, too, as the pilled-up mother who still sees her son as a beautiful child.

There's a little too much plodding exposition in Di Trevis's production, and Ralph Koltai's swastika-based conceptual design does the actors no favours. But where it matters, An English Tragedy is strong, true and emotionally devastating.

THE SUNDAY TIMES

John Peter

This is a hard, harrowing but humane play by Ronald Harwood. As in all his best work, heís writing about people who hide some secret, as well as a sense of guilt for hiding it. The secret of Leo Amery, one of Churchillís ministers, was that his mother was Jewish, and so, therefore, was he. His son John, who was hanged for broadcasting Nazi propaganda from Germany, was a difficult child and became a self-obsessed, neurotic adult, a moral cripple. This is not only an English or a Jewish tragedy; itís about the price the persecuted pay for their secrets.

Di Trevisís production, flawlessly acted, has two master performances. John (Richard Goulding) is a puppet of resentment and of a will that isnít quite his own. You sense that he knows his fatherís secret, though itís never stated; itís his contempt for him, and the loathing of his inheritance, that turned him into a Jew-hater and destroys him. Jeremy Child is Leo, a man living in his own shadow, carrying his impeccable Englishness like a shield from his conscience. Unforgettable and unmissable.

THE TIMES

Benedict Nightingale

Like Lord HawHaw, John Amery made pro-Nazi broadcasts from Germany to Britain during the war. He even visited PoW camps to recruit Englishmen into his Legion of St George, which he hoped would fight with the SS against the Russians. In 1945 he was condemned to death for treason, all without trying to exculpate himself. According to a Times report, he pleaded guilty to every charge, half-smiled, bowed to the judge and, without saying another word, was dispatched to death row.

What motivated his treachery? Why didnít he mount a defence that might have saved him from the gallows? These are questions that have long fascinated Ronald Harwood, who wrote The Dresser, won an Oscar for his screenplay of The Pianist and has just picked up a Bafta, this time for The Diving Bell and The Butterfly; and I suppose they have special frisson because Ameryís father, Leo, was Secretary of State for India and Burma and his brother, Julian, became an MP. Harwoodís answer isnít wholly convincing, but that doesnít matter because it emerges tentatively and speculatively from a play that intrigues and grips.

Itís a rather talky piece. Since it is set after Ameryís arrest, thereís a lot of filling-in of facts and anxious speculation about the present and future, much of it involving Nicholas Rowe as his solicitor, Lucinda Millward as the psychiatrist whom he refuses to see, and Jeremy Child and Diana Hardcastle as his baffled, stricken parents. But when Richard Gouldingís Amery is parading his snobbish, virulent ego, Di Trevisís production comes fully to life. Thanks to this young actorís energy and expertise, you get the impression of a chaotic man-child whose antisemitism and anticommunism are dangerously adult, but whose prime bond is with his teddy bear: a mix of Streicher, McCarthy and Evelyn Waughís Sebastian Flyte.

It says much for Harwood that he seeks to understand rather than merely condemn. Though Amery refused to see the shrinks, their consensus after talking to everyone from nannies to his Harrow housemaster was that he was a psychopath; and Goulding's weird babblings and paranoid ravings would seem to justify that, along with a life that had been louche, rackety, destructive and self-destructive. But whatís especially emphasised is his jealousy of his conventional brother and, more, contempt for a father who had hidden his Jewish origins to advance his political career.

Hence, surely, the title. For Harwood, the English Tragedy is a reticence, a habit of evasion, that had toxic effects. He seems almost to be suggesting that Amery supported Hitler and the death camps because at some dark, mad level he had come to hate himself and his own blood. In effect, he committed suicide, which was why both warders and hangman found him unusually brave. Far-fetched? Perhaps Ė but it makes for striking, stimulating drama.

THE GUARDIAN

Michael Billington

Ronald Harwood is fascinated by questions of identity. His last play, Mahler's Conversion, dealt with the the composer's switch from Judaism to Catholicism. His far superior new work is about the fatal consequences of politician Leo Amery's denial of his Jewish inheritance. My only gripe about a genuinely intriguing play is that it focuses less on Leo than his son, John, who was hanged for treason in 1945.

Starting with John's capture by Italian partisans, the first half builds up a psychological portrait of a Tory cabinet minister's son who broadcast Nazi propaganda from Berlin. As his parents are quizzed by a shrink and solicitor and the man himself by an intelligence officer, we learn that Amery junior's hatred of communists and Jews was the product of a pathological instability.

But it is Leo's admission of his own suppressed ancestry that opens up even more fruitful territory. Harwood suggests that Leo, by conforming to perceived notions of "Englishness" in a time of active antisemitism, helped drive his son into political extremism. Harwood's larger point is that the real English tragedy is an inherited contempt for the alien. But I am not sure it wholly explains John Amery's pathetic downfall.

This is, however, a play that deals with refreshingly big issues. Di Trevis's production, staged on an ingenious Ralph Koltai set composed of swastika-shaped platforms, is also impeccably acted. Richard Goulding, as attached to his teddy bear as Waugh's Sebastian Flyte, brings out all of John Amery's exhibitionist hysteria and arrested development. Jeremy Child, as Leo, movingly shows the epitome of establishment

Englishness confronting his own self-deception. There is sterling support from Diana Hardcastle as his snobbish wife and Michael Fenton Stevens as a probing intelligence officer. Harwood has found in an odd footnote of English history a metaphor for our flawed national psyche.

THE INDEPENDENT

Paul Taylor

At 74, Ronald Harwood is showing no signs of slowing down. He's just won a Best Adapted Screenplay Bafta for The Diving Bell and The Butterfly and he may soon be picking up a second Oscar (his first, in 2002, was for The Pianist). Before that, though, he has unveiled his latest stage play, An English Tragedy, in a powerful production by Di Trevis at the Palace Theatre, Watford. It might look a shade incongruous that a drama with this title is performed on a swastika-shaped stage (the set is by Ralph Koltai). But the focus of Harwood's engrossing, eloquent play is the British fascist John Amery, who was arrested and charged with high treason in 1945. What gives the trial its fascinating twist is that the 33-year-old prisoner in the dock was the son of Leo Amery, a senior Tory, close friend of Churchill and former Secretary of State for India and Burma. In mounting a case for the defence, John's connections were both an asset and a liability, but all efforts were rendered futile when he pleaded guilty. Did he do so to spare his family embarrassment? Or was there a deeper reason? And did his son's conviction prompt any soul-searching in Leo?

Richard Goulding vividly communicates the weird emotional disconnectedness of John, who flounces round his cell and talks to his teddy like an anti-Semitic version of Sebastian Flyte. He also suggests that this pansexual embezzler, alcoholic, bigamist and fantasist is a lost, pathetic figure. Determined to spearhead a crusade against the twin evils of Jewry and Communism, he toured the Allied prison camps recruiting for his soi-disant League of St George, but he only managed to scrape up 57 volunteers. Even his Nazi pals took exception to his drunken sexual escapades.

The play explores the terrible price of concealing one's true identity and living a lie. Jeremy Child as John's father conveys the agony of confronting the fact that his refusal to acknowledge in public key aspects of his heritage may have helped drive his son into self-hating extremism. Diana Hardcastle is heartbreaking as the doting mother. A thought-provoking drama with a compelling subject.