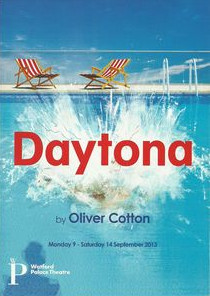

Venue: Watford Palace 2013

Directed by David Grindley

| Happy in

their shared passion for ballroom dancing, Joe and

Elli plan to win the next big competition. But the

unexpected arrival of a figure from their past on

a cold winter's night threatens to throw

everything off balance.When they discover the

story behind his sudden return, Joe and Elli must

confront a profound moral dilemma. |

|

| Cast |

|

| Elli | Maureen Lipman |

| Joe |

Harry Shearer |

| Billy |

John Bowe |

Maureen Lipman, Harry Shearer, John Bowe

Reviews

Time Out

(2/5 stars)

There are about three plays struggling to get out of Daytona and only one of them is any good. Trying to cover senior ballroom dancing, the Holocaust and a decades-old love triangle would be a daunting challenge for any writer. Most would, sensibly, walk away from it. By refusing to do so Oliver Cotton has produced a few good moments of theatre that are sadly submerged in the equivalent of dramatic Horlicks.

This despite an extraordinary cast for whom most directors would sell their grandmothers. Harry Shearer, of The Simpsons fame, plays Joe, a cardigan-wearing accountant. He is happily dominated by the fabulous Maureen Lipman as Elli, a wife who wears not just the trousers but also the high heels and sequins. On Ben Stones’ delightfully dour set, all oranges, beiges and lino, we see them on the eve of a big dancing competition. The arrival of John Bowe’s Billy – the brother who Joe hasn’t seen for 30 years – creates a crisis at the same time as stirring up an alarming range of memories.

There is only one good reason for going to Daytona, and that is to see Lipman’s performance as a woman who has to live with the fact that the brother she married was not the one who was the love of her life. She cracks out the script’s few one-liners with her usual panache, but it’s the pathos of her heartbreak that grips the audience. Bowe puts in a valiant turn as Billy, while Shearer throws himself rather too convincingly into the role of downtrodden accountant. Yet the inescapable problem of the evening is a piece of writing that tries to blend wit, profundity and history, but ends up as the equivalent of chronic dramatic indigestion.

* *

* * *

Oliver Cotton’s play Daytona is overfull of things vying for focus and empathy, and audiences are likely to be more frustrated by what is left insufficiently explored than satisfied by what gets the play’s full attention

* * * * *

The Times

(4/5 stars)

Oliver Cotton’s new three-hander Daytona features one of the most intelligent trios in town: Maureen Lipman and John Bowe are joined by Harry Shearer, whose credits run from Spinal Tap to The Simpsons (as the voice of Burns, Smithers and Flanders). For each in turn, it is a dazzling showcase.There are long, emotionally charged narrative monologues (each has more than one), demanding from the others the equally difficult art of listening and reacting. For 45 minutes in the first act, Lipman is off stage and Shearer hardly gets a word in, as Bowe — his younger, bigger and more chaotically dressed brother, Billy — barges into his evening after a 30-year disappearance with a long and apparently pointless holiday anecdote, culminating in a very sharp point indeed. But while he tells it, you watch Shearer as much as Bowe. That’s classy.I won’t spoil the shock, so circumspectly say only that Lipman (Ellie) and Shearer (Joe) are a Jewish couple in their seventies getting ready for a senior ballroom dance competition in 1980s Brooklyn (the decade is a clue). Billy turns up in a Hawaiian shirt under an ill-fitting tweed suit, sockless and animated, unapologetic about wrecking their business by his disappearance in the 1950s. He has a shocking bit of news, related to what happened half a century ago on another continent and an event two days ago in a resort hotel on Daytona Beach.

Quite apart from the big bad news, there is private emotional history to untangle; betrayals on many levels. Cotton plays with the fact that it is not only criminals but victims who may reject old identities, lest victimhood itself become a badge. There are outbreaks of sudden shocking rage and grief (I have never seen Lipman stronger). Yet it is not a bleak play but a thoughtful, sharp one, well aware of the absurdity within tragedy and the potential gulf between male angst and dry female pragmatism (Lipman, of course, is mistress of the latter). A meditation, too, on long life and the need to come home to old alliances, if only to let them go.The director is David Grindley, fresh from his success with another treatment of the psychological fallout of war, The American Plan. It would be tempting to say that he only needed to let these three get on with it, but I suspect there was much more to it than that. He certainly offers extraordinary, animating moments to remember: and not just Lipman hurling Chinese takeaways at her husband. Though I did enjoy that bit, a lot.

The Daily Telegraph

(4/5 stars)

Oliver Cotton’s new play Daytona, which finds the much loved Maureen Lipman in first-rate form. It is however a devil of a play to write about. Though not exactly a thriller much of its impact depends on two big dramatic reveals. So I will follow the convention of whodunit reviewing and confine my description of the plot to the first act, and you will just have to take it on trust that the second half is equally absorbing.

The action is set in Brooklyn in 1986, in the apartment of Joe (Harry Shearer) and his wife Elli (Lipman) a Jewish couple in their early seventies. Joe still does a little accountancy work but their passion is for ballroom dancing and we see them practising some nifty moves at the start of the show in preparation for a “seniors” competition the following night. They niggle at each other a little but are clearly close and content with their lot, but while Elli is out picking up her ballroom dress, Joe’s brother Billy (John Bowe) arrives.

The siblings haven’t seen each other for more than 30 years and the cause of their estrangement is one of the play’s puzzles. But Billy, bizarrely dressed in a winter coat and a Hawaian shirt has urgent news to impart. While spending the winter at Daytona Beach in Florida, he recognised one of the guards at the concentration camp where all three characters were incarcerated by the Nazis. He was a man who shot people at random and beat prisoners to death with a spade. Harry bought a gun, conducted an execution in the hotel swimming pool, escaped in the subsequent confusion and is now seeking sanctuary with his brother.

It is a gripping story, powerfully told and excellently performed. Bowe, a great shambolic bear of a man, superbly captures Billy’s mixture of elation and confusion as he knocks back the whisky, too wired to know whether he has done the best or the worst thing in his life. Meanwhile Shearer suggests the guarded antipathy Joe feels for his brother who has turned up in such dramatic circumstances and expects to be helped out. Infuriatingly I cannot write much about Lipman’s performance without giving too much away, but after initially treating Billy with glacial politeness she plumbs moving depths of emotion and pain as she is forced to confront both the current crisis and the painful secrets of the past.

David Grindley finds all the play’s considerable strengths, including its many moments of sharp humour, and persuades the audience to suspend its disbelief when the plot veers towards the implausible. This is a compelling and deeply humane production and one I warmly recommend.

* * * * *

Metro

(3/5 stars)

Septuagenarian couple Joe (Harry ‘Spinal Tap’ Shearer) and Elli (Maureen Lipman) lead a settled existence in Brooklyn, where the main focus of their days is ballroom dancing. Their life could hardly be more peaceful – until Joe’s younger brother, Billy (John Bowe), makes an unexpected visit and says he is on the run after killing a man in Florida.

Oliver Cotton’s wordy three-hander is set in the 1980s but the action driving the dialogue takes place offstage and, for the most part, decades before Billy’s gunning-down of an old tormentor. Crimes on both a domestic and public scale – adultery, betrayal, the Holocaust – form the backdrop to the reunion between the chalk-and-cheese siblings. But despite the weightiness of the political and emotional material, Cotton’s script struggles to make the dramas of the past come to life in the present.

The first half of the play is dominated by a long monologue in which messy, mercurial Billy – in a Hawaiian shirt and ill-fitting suit and bearing copious amounts of Chinese takeaway – tries to justify his behaviour to neat, controlled Joe. It’s simultaneously meandering and overpacked with narrative. The second half is better and brings Billy’s relationship with Elli centre stage. The story never quite coheres, even though David Grindley’s production boasts a terrific cast. Lipman’s Elli, in particular, is a splendid creation, at once stubbornly matter-of-fact and slyly sensual.