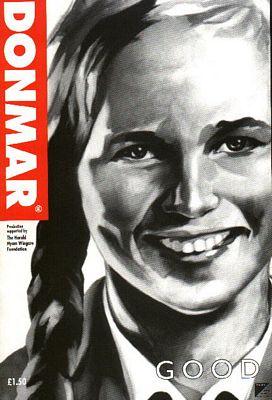

GOOD by C.P.Taylor

Venue: Donmar Warehouse 1999

Directed by Michael Grandage

Venue: Donmar Warehouse 1999

Directed by Michael Grandage

Cast in order

of appearance

| Halder | Charles Dance |

| Sister Elizabeth |

Eva Marie Bryer |

| Mother | Faith Brook |

| Doctor Bouller |

Peter Moreton |

| Maurice | Ian Gelder |

| Helen | Jessica Turner |

| Anne | Emelia Fox |

| Freddie Hoss |

Benedict Taylor |

| Hitler Eichmann |

John Ramm |

| Clerk Bok |

Cymon Allen |

Review

Sunday Times: Benedict Nightingale

Rise and fall of a philosophical Nazi

Sunday Times: Benedict Nightingale

Rise and fall of a philosophical Nazi

C.P.Taylor's Good is on the National Theatre's list of the century's 100 best plays, and even a less-than-brilliant revival cannot undermine my belief that it merits a place near the very top. If a grandchild or a Martian asked me how the nation of Beethoven and Goethe came to perpetrate the greatest of crimes, I would suggest they saw or read it. Good was the last of Taylor's plays to be performed before his death in 1981 and it remains his boldest, for in it he used all his sympathetic imagination to enter the mind of a man who ends up helping to organise the slaughter of his, Taylor's, fellow-Jews.

Since the piece starts about 1933, finishes in 1941, and shows the Darwinian process by which a pleasant professor of literature evolves into an Auschwitz functionary, the play could have been numblingly schematic. Instead, it bubbles with restless energy, brims with wry but pointed observation. There are sudden switches of time and place, abrupt shifts from monologue to dialogue and, less happily, from song to speech. But the forward thrust is unstoppable, and the effect is to leave you wondering if you too could rationalise and deceive yourself into the abyss.

Charles Dance's Halder is impelled by a senile mother to write a novel advocating euthanasia and by a chaotic, demanding wife to safeguard his career by joining the party. Soon he is being courted by Nazis in search of helpful intellectuals and persuaded to exercise his "humane but unsentimental strengths" first in a subnormality hospital, eventually in far darker places. After all, if he is supervising the burning of books, or watching SS men smash Jewish homes, or putting Eichmann's orders into practice, he can minimise the thuggishness.

Halder's need to believe in his own compassion leads him into moral and mental contortions galore. The extermination of incompetents is a kindness, if only the gas-chamber is disguised as a bathroom. Anti-Semitism is a politically expedient aberration that, like Hitler himself, will soon pass. Jews are remarkable people, but they have shaped a literary tradition that is fixated on the individual, and have brought their agonies on themselves. Isn't it simplistic to think either that they are victims or that "good" is an objective absolute?

Taylor intended his attack on compromise to extend to you, me and himself, and from the past to the present and into the future; but Michael Grandage's revival sometimes leaves one feeling uneasy in the wrong way. There is little wrong with the supporting performers, who include Emilia Fox as Halder's eamest young lover and Ian Gelder as the increasingly distraught Jewish friend he insidiously betrays. But though he manages to seem plausibly decent even when elegantly attired in SS togs, Dance lacks the insecurity, the vulnerability and finally the unacknowledged despair of the Faustian weakling Halder. But never mind. It is a part, and Good, a play that will be tackled again and again and again.