THE THREEPENNY OPERA by

Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill

Venue: Donmar Warehouse 1994

Directed by Phyllida Lloyd

Venue: Donmar Warehouse 1994

Directed by Phyllida Lloyd

Cast

| Mr Peachum | Tom Mannion |

| Mrs Peachum | Beverley Klein |

| Polly Peachum | Sharon Small |

| Macheath | Tom Hollander |

| Filch Ned |

Ben Albu |

| Matt | Simon Walter |

| Jake | Jeremy Harrison |

| Walt PC Smith |

Terence Maynard |

| Tiger Brown | Simon Normandy |

| Lucy Brown | Natasha Bain |

| Jenny | Terence Hugo |

| Rev Kimball | Amanda Edwards |

| Company | Kate Edgar Dawn Michael Caroline Hall Kevin Davy Paul F Girbow |

Feature

Daily Telegraph : Michael Church

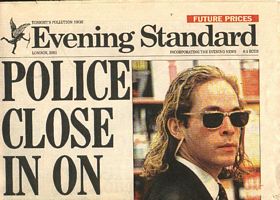

“POLICE CLOSE IN ON MACK THE KNIFE" shouts the tabloid page stuck up on the rehearsal room wall. “If convicted, he could face televised execution," hisses the caption to its photo of a long-haired wide-boy in dark glasses In a corner of the room a girl is being realistically throttled by a thug, while the wide-boy looks on approvingly. Meet the cast of The Threepenny Opera, getting into the mood. The spoof cutting is there to remind them of their purpose, which is to create a plausible near-future. The Prince of Wales has retired to a monastery, his elder son is about to he crowned king, and the police are worried that this happy event may be marred by a huge army of beggars. The coronation, moreover, is faced with a rival attraction: an execution is to be televised, and smart Londoners are queuing for a place in the studio audience.

If you attend the show, which opened this week at the Donmar Warehouse, Covent Garden, be prepared to be filmed as part of the proceedings. State-of-the-art surveillance cameras have been installed in the gallery - this is theatre in the round - and dotted through the audience. The other aspect of the future which director Phyllida Lloyd and designer Vicki Mortimer convincingly portray is the monitoring by the police of everything that moves. No matter that this classic comedy-with-songs was written for Berlin in 1928. No matter that The Threepenny Opera was itself a mere translation - albeit a free and inventive one of The Beggar's Opera which John Gay wrote for London in 1728. Gay and his German successors were animated by the same radical passion, and it is that passion which animates the London production now.

"We want to make people think a little, feel differently about the world," Lloyd says. The fact that the Donmar is surrounded by London's biggest concentration of beggars is in Mortimer's view a happy coincidence, as is the show's timing. "The streets of the redeveloped, slicked-up Covent Garden will be full of Christmas consumer-mania. The audience will walk out into exactly the situation the play-is describing." But whose play? "Book and lyrics by Bertolt Brecht. Music by Kurt Weill," says the programme. Nobody would dare question Weill's authorship of the show's immortal songs. But, as a new book has pointed out, Brecht's name on the banner is problematic. In The Life and Lies of Bertolt Brecht, John Fuegi shows that 80 per cent of the text was written by Elisabeth Hauptmann, one of several women who tried to snare the writer into marriage through providing him with dialogue to which he eagerly attached his name.

Not even all the lyrics are his. Some are by the 15th-century murderer-poet Francois Villon, while others are from Kipling reworked by Hauptmann (admittedly then reworked by Brecht). But Brecht did write Mack The Knife, so we can forgive him much. So potent was this song’s influence in the Threepenny Opera-mania which swept America and Europe in 1930, that a New York radio station took the song off the air in an attempt to stem the flood of copy-cat knifings it was said to inspire.

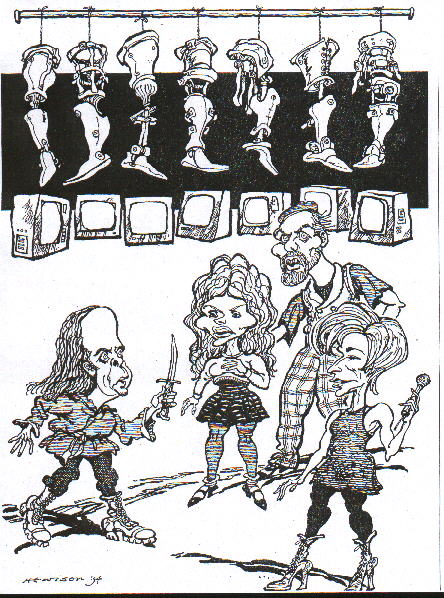

The plot turns on a gangland feud. Macheath has just marred Polly Peachum, whose father runs a lucrative begging business. Tiger Brown, the chief of police, is a close mate of Macheath's, but Peachum - furious over the theft of his daughter - blackmails him into imprisoning the charismatic outlaw. But since "this is not real life, but opera", as Brecht - or rather Hauptmann - puts it, Macheath gets off, and all ends happily. The Donmar Macheath, played with power-packed menace by Tom Hollander, is no mere barrow boy: he moves with ease through all levels of society. Its Peachum is a media baron, running a model agency for beggars. As Lloyd points out, such things may already exist: she and her company have noted the way their real-life exemplars fall into specific categories. "No one is suggesting that the women with babies, the alcoholics, or the Bosnians are malingering, but it looks as if many may be caught in protection rackets." The stage unfortunates come to Peachum for "styling' ', for fake prosthetic limbs, and to have scars and bruises applied, in return for which he creams off their takings. The analogies with Fagin now doing a roaring trade at the Palladium - are striking. This is indeed, as Lloyd says with a laugh, the ''Threepenny Oliver".

Reviving a work so heavy with history, the musically versatile Donmar company has been surprisingly unfazed. "If Sting and Roger Daltrey can do Macheath, then I certainly can," Hollander says. Sharon Small faces an even greater challenge as Polly, a part made famous by Lotte Lenya and more recently Ute Lemper. Small plays the part in her native Scots tone, with raw sincerity and anger. This production may well emulate its Berlin forerunner by becoming the smart thing to see among those it seeks to satirise. But, in the long term, its biggest star may turn out to he a humble translator -not of the main text (ably done by Robert David Macdonald), but of the lyrics. Jeremy Sams's specimen translations were initially vetoed by the Brecht and Weill estates. These bodies insist on owning - and taking most of the royalties from any translation to which they give their approval. It took immense persistence to get them to relent. "If it doesn't sound like a translation, then I'll have succeeded," said Sams last week. It doesn't; he has; and how!

Arnie

Goldstein was garrotted

For his cufflinks and a ring

The Savoy was full to bursting

Strange that no one saw a thing

For his cufflinks and a ring

The Savoy was full to bursting

Strange that no one saw a thing

Yes, today's authentic note. Sams has provided patter-songs worthy of W. S. Gilbert and ballads redolent of Kipling. He may not own his own work, but I predict a long life in the anthologies.

Daily Telegraph: Charles Spencer

Mack is back to the future

Even those, like myself, who normally can’t stand Brecht have to admit that The Threepenny Opera has a great deal going for it. It was written early in Brecht’s career, before he lapsed into Marxist hectoring. The fact that he based the show on Gay’s Beggar’s Opera ensured that he had a compelling story to tell, while Kurt Weill’s tunes, reeking with sweetness of corruption, lodge potently in the memory. Director Phyllida Lloyd has refused to treat the musical as a period piece. The plot demands that the action takes place at the time of an English coronation, and she has moved the action forward to the London of 2001, at the time of the Coronation of Prince William. The updating works superbly. London in 2001 is very like the London of 1994 but even more horrible. Surveillance cameras proliferate and the stage is surrounded by TV monitors.

Tom Hollander (Macheath), Sharon Small (Polly Peachum), Tom Mannion (Mr Peachum), Tara Hugo (Jenny Diver)

Jeremy Sam’s excellent new lyrics are bang up to date. We learn of Asians dying in arson attacks, of sanctimonious Tory ministers with a taste for crumpet, of “the British army making salami from Basra to Goose Green”. As angry agit-prop, the show pulls no punches. Unfortunately the playing of the band is pretty rough and some of the singing is weak. I have no such complaints about Tara Hugo, though, who delivers a chilling, mesmerising account of the show’s best number, Mack the Knife, now known as The Flick-Knife Song.

Tom Hollander, who famously played Celia in an all-male As You Like It, seems like unlikely casting as the villainous Macheath. But with his insolent manner, dead eyes, and sudden moments of psychopathic violence, he is compulsively watchable. There’s strong support from Tom Mannion as a Glaswegian Peachum of grotesque sleaze, from Berverley Klein as his simperingly demure wife and Sharon Small as a splendidly sexy Polly. Yet for all the merits of both show and production, I still can’t overcome my aversion to Brecht. He wants to save humanity while actually despising it, and though the show is meant to inspire compassion for the dispossessed, its cynicism leaves a repellent taste in the mouth.

Times: Benedict Nightingale

Brecht to the future

As we know now, Brecht regularly stole other people’s work; but in the case of The Threepenny Opera he openly admitted that his source was John Gay,. Whether his plagiarism of The Beggar’s Opera was necessary or effective is another matter. Without Weill’s music you have a script that adds surprisingly little to the original. Indeed, previous productions have left me feeling that Gay’s point, that the lower depths are no more rackety than the upper social slopes, gets muzzled not sharpened during its journey through Bertolt’s doctrinaire conscience.

But Phyllida Lloyd’s spendidly inventive revival forces us doubters to think again. True she has taken liberties with The Threepenny Opera, including the rather serious one of cutting the scene in which Macheath’s wife, Polly Peachum, transforms his crime syndicate into a “respectable” banking business. But could she have achieved as much with 18th-century English as she does with Robert David Macdonald’s colloquial translation of modern German? Gay did not provide her with the same opportunity to stage what we get at the Donmar: 2001, A Spiv’s Odyssey.

Her futurism makes an advantage of much that now seems irrelevant or anachronistic in Gay and Brecht. Prince William is about to be crowned. The death penalty has been restored, though Macheath faces electrocution in front of a gloating TV audience instead of public hanging. And beggary and crime have spread and spread until destitutes are organising demos that tax police violence to the limit. Can we really be sure this won’t be London in six years’ time? One could argue that by equating Peachum’s army of vagrants with our own homeless, Lloyd inadvertently suggests what recent evidence has tended to disprove: that those cadging alms in the Strand are actually a well-orchestrated load of petty profiteers. But that is not an objection likely to linger in the mind, for her revival is a lot harder hitting than others I have seen. “Victoria’s getting poorer than Calcutta,” rasps Tom Mannion’s Scottish Peachum in “Life’s a Bitch”, as the song “The World is Hard” has been retitled; and on slither shapes in dark sleeping bags, presumably to join his mainlining boy-tramps and girls with placards of “I have Aids, hug me” round their necks.

Macheath himself is played by Tom Hollander, on the face of it an odd casting for the gentle earnest actor I recall as Celia in an all-male As You Like It. But helped by a tiny moustache, a scar and an Essex-accented sneer, he gives a marvellous unsentimental performance. This is no gentleman-buccaneer surrounded by like-minded outcasts, but a mean, sly hood protected by louts in leather and sincere only when he sings “you have to kill your neighbour to survive, it’s selfishness that keeps a man alive”. The actors mourning or accelerating his journey to death-row are less impressive, though Tara Hugo’s Jenny Diver makes an impact when she ironically celebrates his feats in lyrics as black as her petticoat. Again, Weill’s music seems less textured than it might be. Even in the bland National revival in 1986, it left me thinking of coins, chains, the rattle of keys and the sound of bones being loaded into carts; here it seems too cool, dry and thin. But helped by Macdonald’s abrasive text and Jeremy Sam’s bold, witty rhymes, the production overcomes weaknesses that would sink many others. It is brisk and brazen, pointed and punchy, and altogether better than Brecht deserves.