More Plays and Shows

Back ◄ ► Next

Back ◄ ► Next

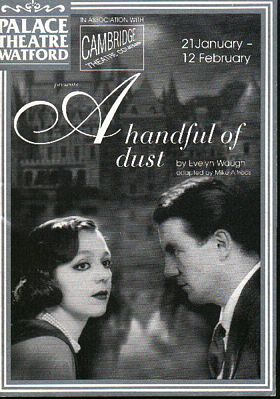

A HANDFUL OF DUST by Evelyn

Waugh

Adapted by Mike Alfreds

Venue: Watford Palace 1994

Company: Cambridge Theatre Company

Director: Mike Alfreds

Adapted by Mike Alfreds

Venue: Watford Palace 1994

Company: Cambridge Theatre Company

Director: Mike Alfreds

| John Beaver Allan etc |

Mark Aiken |

| Mrs Beaver Nanny etc |

Marty Cruickshank |

| Jock Grant-Menzies Reggie St Cloud etc |

Laurence Kennedy |

| Tony Last | Tim Dutton |

| Brenda Last | Annabelle Apsion |

| John Andrew Dr Messinger etc |

Jason Watkins |

| Ben Mr Todd etc |

Ian Price |

| Marjorie Millie etc |

Sophie Heydel |

| Polly Cockpurse Mrs Rattery etc |

Sally Knyvette |

| Jenny Abdul Akbar Winnie etc |

Pamela Moiseiwitsch |

Article on an earlier production of this adaptation also directed by Mike Alfreds at the Lyric, Hammersmith, in 1982

Sunday Times: James

Fenton

Going by the book

Going by the book

Can any novel in theory be adapted for the stage? The wise answer to this question is yes; to say no is only to invite some brilliant refutal. War and Peace seems a pretty tall order for the theatre yet there it is, currently playing at the Coliseum, gigantic, convincing and unmistakably a representation, however partial, of the novel. The fact that it is an opera might seem, on paper, even more far-fetched, but there are moments when Prokofiev tells us, through music, things we could feel in no other way – he tells us, for instance, what it is like to feel your life ebbing away.

The RSC Nicholas Nickleby, a famous stage success, threw in a play and an opera within a play. It exploded the limits of scale, and found an audience eager to see it not once but again and again. Scale, however, is the nub of the problem. A Handful of Dust is not a long book, nor is this production at the Lyric Hammersmith exorbitantly long. Nevertheless you emerge from the theatre feeling that the experiment has outstayed its welcome. It’s not that some bits are strikingly less good than others. Rather the staging has lost its power to surprise and continually amuse.

Mike Alfreds, the director, offers at the start a kind of contract with the audience: he will give a faithful and full rendition of Evelyn Waugh’s novel as long as we accept certain conventional restrictions. We are allowed a design but no props beyond chairs. We are offered a high quality cast, but there are only ten of them. If we accept these conditions we will watch the novel spring to life, but we will continually be led back to the text itself. The actors share out snatches of narrative, wittily spliced with dialogue. But we will always be conscious that the actors are acting, vividly slipping into each new role that offers itself.

This means that the piece becomes a kind of display of skills. What the company has gone for is style, style, style. The Twenties voices are beautifully recreated, the gestures charmingly observed. Emotion is in short supply, and that becomes a problem, but one can see that the problem emanates from the book itself. Waugh’s great trick in his early novels was to deny his characters the emotion appropriate to the moment, and his plots the happy outcome of convention. It is a trick learnt, surely, from Saki, whose “Unbearable Bassington” is so similar in construction to A Handful of Dust. Waugh’s cruelty to his characters is nowhere more neatly demonstrated than his abrupt bumping off of the tiresome young son of Tony and Brenda Last: first he tells the reader, “I hate this character,” then he proves his hatred in excess of expectation first by disposing of the child and then by demonstrating his mother’s defective feelings on hearing news of the death. But the actual behaviour of the omnipresent novelist is itself cruel. Waugh does not simply prove that people are nastier than you think – he also demonstrates that novelists can be nasty too. We are asked to sympathise with Tony Last, as much on the basis of his feeling for his property as for his sorrow over his lost son.